BROUGHT TO YOU BY:OK BUT WHY?

LEAD ARTIST:

ISLENIA MIL

@ISLENIAMIL

We like to think of ourselves as open-minded much more than we like to change our minds.

At The Plenary, we used to believe that by helping scientists become better communicators, we could build meaningful bridges between science and people who weren’t particularly interested in it. For years we toured university campuses and built our name on the importance of “outreach”. But we were wrong.

We were stuck in a common way of thinking that many researchers call the “deficit model”. It’s the idea that people don't support or incorporate science into their beliefs because of a lack of knowledge, and that giving them more information will fix that. The research shows that model doesn’t work – or at least, not on its own. People don’t form beliefs based solely on what we know or don’t know. We form them based on our identities, the social influences around us, our emotions, experiences, and imaginations. By the time we become adults, what we believe is rarely based solely on what we know. And what we learn is rarely based solely on the evidence we encounter. It’s much more often a matter of changing our minds.

A lot of the systems that surround us were designed to solve different problems or serve different values than the ones we need today, yet we have a hard time letting go. Most of us have strongly established worldviews and beliefs, and these can become obstacles for new information. Our culture sends mixed messages about openness. It’s an insult to call someone “closed-minded”, yet we’re also taught to value conviction and certainty over fluidity and changing our minds.

We all love the idea of being open, but if we want to make it a reality, we have to get a lot more comfortable with the discomfort that comes with it.

QUICK VIEW

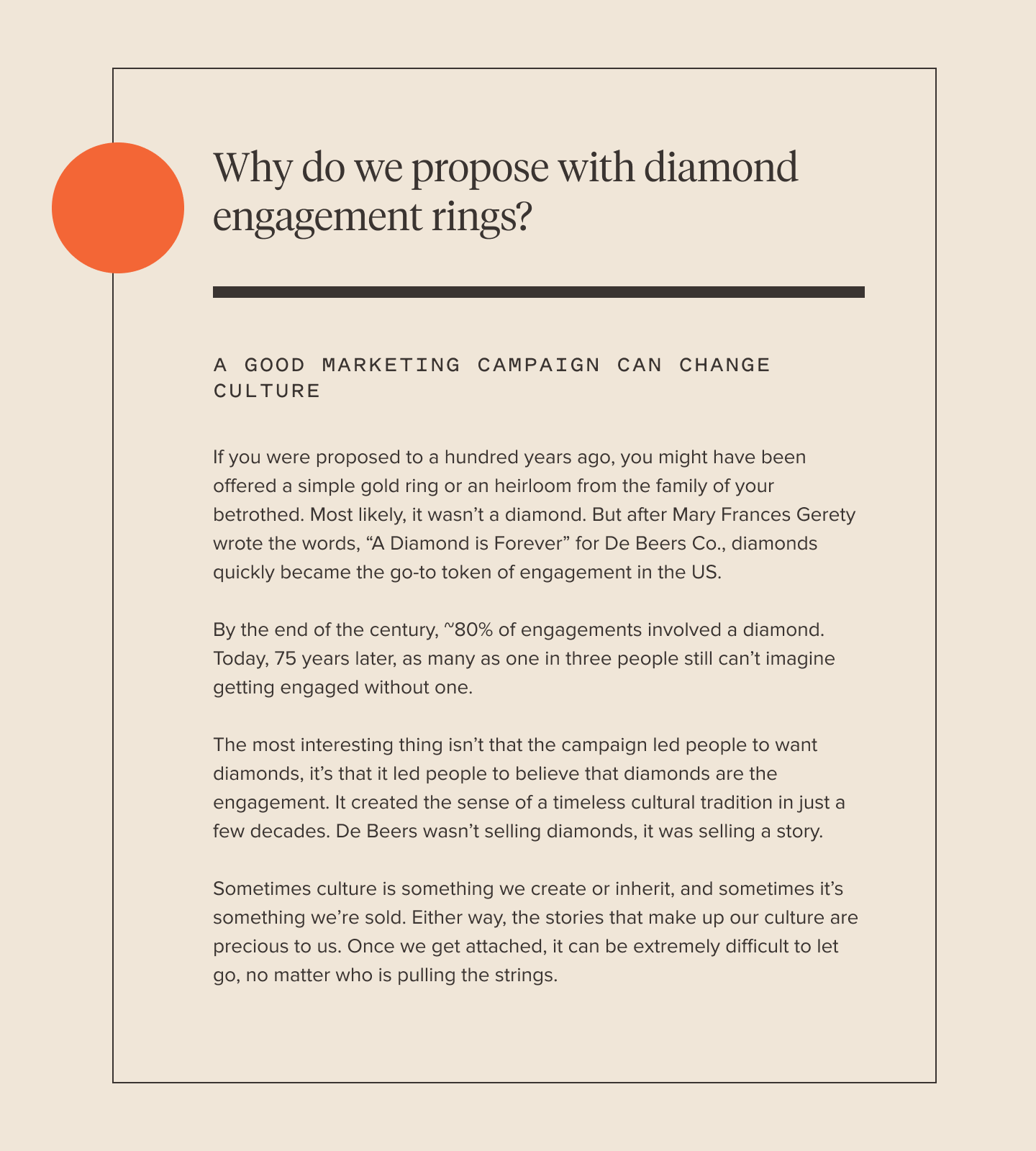

Why do we propose with diamond engagement rings?

A GOOD MARKETING CAMPAIGN CAN CHANGE CULTURE

If you were proposed to a hundred years ago, you might have been offered a simple gold ring or an heirloom from the family of your betrothed. Most likely, it wasn’t a diamond. But after Mary Frances Gerety wrote the words, “A Diamond is Forever” for De Beers Co., diamonds quickly became the go-to token of engagement in the US.

By the end of the century, ~80% of engagements involved a diamond. Today, 75 years later, as many as one in three people still can’t imagine getting engaged without one.

The most interesting thing isn’t that the campaign led people to want diamonds, it’s that it led people to believe that diamonds are the engagement. It created the sense of a timeless cultural tradition in just a few decades. De Beers wasn’t selling diamonds, it was selling a story.

Sometimes culture is something we create or inherit, and sometimes it’s something we’re sold. Either way, the stories that make up our culture are precious to us. Once we get attached, it can be extremely difficult to let go, no matter who is pulling the strings.

REFLECT

Why do we celebrate birthdays annually instead of marking other life milestones? What could we mark instead?

Why do we think we’re left- or right-brained?

SCIENTIFIC IDEAS CAN GET LOST IN THE GAME OF TELEPHONE

In the 1960s, scientists studied a group of epilepsy patients who had undergone an unusual treatment: the structure that connects the two sides of their brain was surgically severed. This gave scientists a unique window into the role that each side of our brain plays in our behaviors. Turns out, both of them are involved (in slightly different ways) in just about everything that we do.

Over the next half century, these findings got trapped in a grown-up version of the “game of telephone”. They were sensationalized by press releases and media outlets. They were distorted by blogs and word-of-mouth. And today, most people believe that they’re either left-brained or right-brained, because at some point, that’s what they were told.

A lot of the information that we encounter has already passed through similar filters. It starts with a kernel of truth that’s arbitrarily cut, boosted, and crafted to maximize its curb appeal. The problem is, once it’s catchy enough to catch on, it can be extremely challenging to debunk. As the neuroscientists battling the left-brain / right-brain myth can confirm, the truth is rarely catchy enough to fight back.

REFLECT

Why do we take the health of every other organ more seriously than brain / mental health? Where does that value come from?

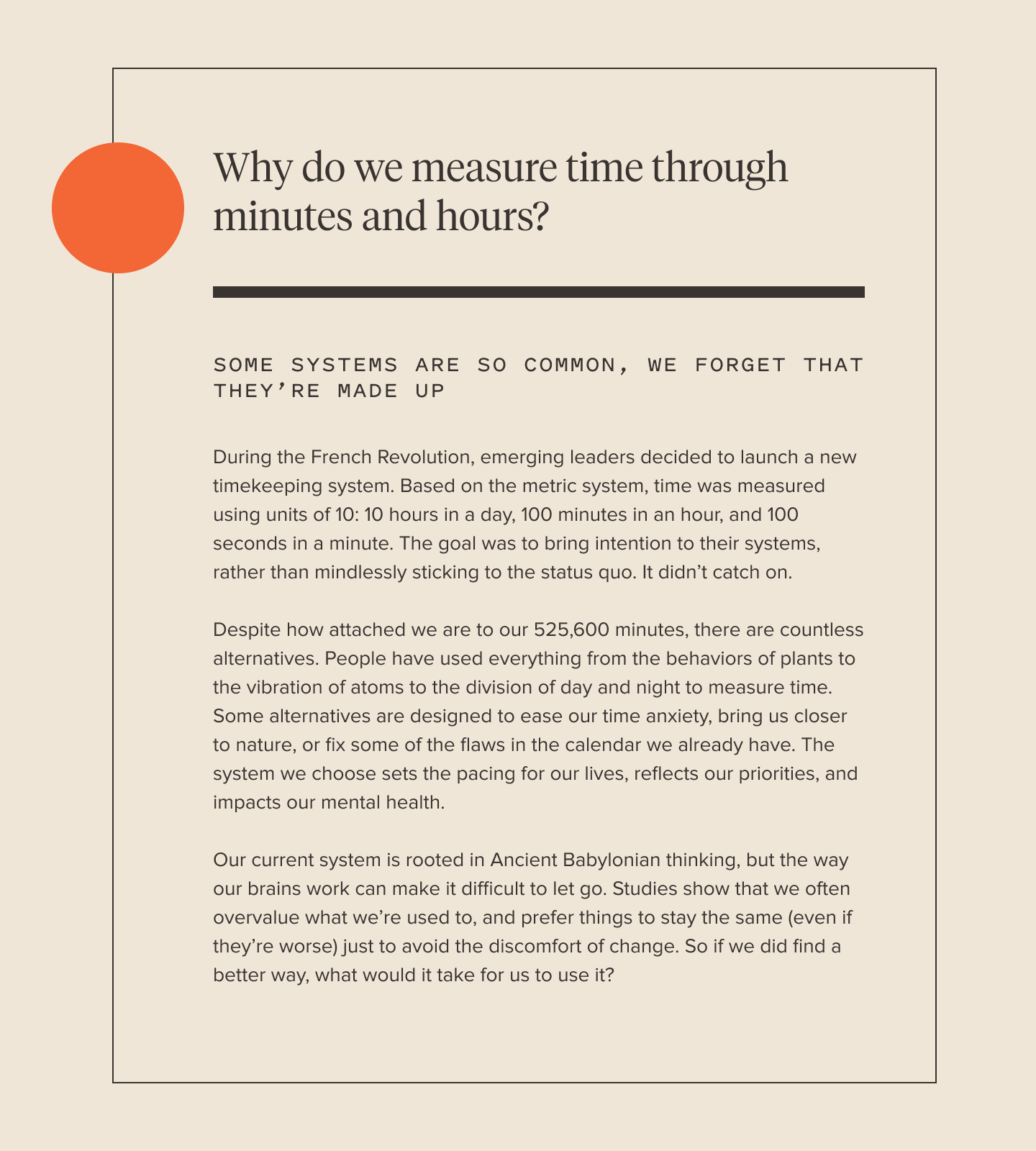

Why do we measure time through minutes and hours?

SOME SYSTEMS ARE SO COMMON, WE FORGET THAT THEY’RE MADE UP

During the French Revolution, emerging leaders decided to launch a new timekeeping system. Based on the metric system, time was measured using units of 10: 10 hours in a day, 100 minutes in an hour, and 100 seconds in a minute. The goal was to bring intention to their systems, rather than mindlessly sticking to the status quo. It didn’t catch on.

Despite how attached we are to our 525,600 minutes, there are countless alternatives. People have used everything from the behaviors of plants to the vibration of atoms to the division of day and night to measure time. Some alternatives are designed to ease our time anxiety, bring us closer to nature, or fix some of the flaws in the calendar we already have. The system we choose sets the pacing for our lives, reflects our priorities, and impacts our mental health.

Our current system is rooted in Ancient Babylonian thinking, but the way our brains work can make it difficult to let go. Studies show that we often overvalue what we’re used to, and prefer things to stay the same (even if they’re worse) just to avoid the discomfort of change. So if we did find a better way, what would it take for us to use it?

REFLECT

Why are calendars organized by months and not by moon cycles or seasons? How might other options impact our lives?

Why is tipping such a big part of our culture?

SYSTEMS TEND TO STICK AROUND MUCH LONGER THAN BELIEFS

In Medieval Europe, the class system was rigid. Aristocrats inherited and held the majority of the wealth, power, and land. Most people were serfs with limited rights, little to no pay, and an obligation to serve. Tipping was largely a way for aristocrats to reinforce their status and incentivize good service from poorly paid workers – a practice that remained prevalent even as the aristocracy fell.

By the 19th century, many Europeans began to reject the practice in favor of guaranteed fair pay, just as wealthy travelers from the United States began to adopt it. After the Civil War, many employers in the US saw tipping as a way to justify paying low wages to formerly enslaved individuals, which looked a lot like the practice’s Medieval origins.

Despite eventual public pushback and a brief stint of anti-tipping legislation, industries that benefited from tipping successfully lobbied to favor it in our laws, creating a service industry that, in many ways, now depends on it.

Today, tipping is one of many everyday systems that was originally designed to help those with power hold onto it.

REFLECT

Why do we still use daylight saving time in many places? What would happen if we didn’t?

Why do we think pink is for girls and blue is for boys?

MANY OF THE NORMS WE THINK ARE TIMELESS ARE ACTUALLY PRETTY NEW

If gender reveal parties were a thing in 1918, you may have cut a blue cake for girls (because blue was “dainty”) and a pink cake for boys (because pink was the “stronger” color). Even then, most people wouldn’t have cared. That’s because we didn’t start seriously color coding our babies until the mid-1940s.

Genders and the expectations that come with them vary wildly across time and culture. High heels got their start in fashion as a symbol of masculinity and status for wealthy men. In some places, property is passed from mother to daughter, women are the primary hunters, or many genders have been recognized since ancient times.

While some norms may be rooted in religious beliefs, many are rooted in the latest ad campaign or cultural moment. We constantly look to each other, without realizing it, to figure out how we’re supposed to be. And when enough people like us think something, we often start to think it too.

The result is an ever-changing set of social rules that we instinctively put on ourselves and each other, even if we never knew why we were following them in the first place.

REFLECT

Why is there often a separation of living spaces based on age, like retirement homes or student dormitories? What might it be like if we changed that?

Why do we imagine aliens as “little green men”?

THE FUTURE IS SHAPED BY SHARED IDEAS OF HOW THE WORLD COULD BE

Toxic chemicals glow in the dark. Abandoned Victorian homes are probably haunted. Pandas are sweet and cuddly. And of course, aliens are little green men.

Even if you know these ideas aren’t technically true, if you grew up surrounded by popular culture in the US, you probably recognize them.

The beliefs, feelings, perceptions, and ideas that a community shares is often called an “imaginary”. We can share imaginaries around anything – technology, politics, space and time, the environment. And they’re immersive. They’re usually so deeply embedded in our identities and assumptions about the world, that even though we rarely notice them, they’re influencing what we think of as important, valuable, or even achievable.

The most dominant imaginaries of a culture can shape everything from laws to the way a city is built. By noticing and questioning the forces that shape our collective imaginations, we have a much better chance at expanding our shared idea of what’s possible.

REFLECT

Why do many of us work five days a week and rest for only two? What are the alternatives?

Stay open.

It can be extremely difficult to keep an open mind, as our culture and cognitive biases can get in the way. One way to get better at it is to practice and look for models of open mindedness in others. We have to normalize being wrong or changing our minds by exchanging those stories freely.

Take some time to brainstorm and journal some questions you have lingering in your mind.

Then, think about some things you’ve changed your mind about. What led to the change? And what are some of the forces that led you to hold on as long as you did? What are some of the things that these forces may be keeping you attached to today?

BRING HOME THE EXHIBIT

SIGNATURE SCENT

Anise, Saffron, Black Current, AmberWe partnered with Casita Michi to create custom, limited edition candles inspired by the themes of each exhibit.

SIGNATURE COCKTAIL

suze, aperol, lemon, simple syrup, jalapeno, soda waterThe baristas at The Foundry created custom cocktails (and mocktails) inspired by the themes of each exhibit. Incorporate their recipes into your home gatherings to get a taste of the exhibit.

MEDIA RESOURCES

What to check out next.

WORD BANK

“The future doesn’t just happen. It’s built.”

— Crystal Dilworth, PhD

science communicator & Neuroscientist

“ok but why” contributor

SCIENCE SPOTLIGHT

The reason we avoid the pains of uncertainty.

Why are we so uncomfortable with uncertainty? A study from 2016 sparked a conversation about the ways humans react to uncertainty[1]. Their experiment subjected people to mildly painful electric shocks either 100%, 0% or 50% of the time as they played a computer game. The researchers found that people’s stress levels were higher when they knew there was a small chance they would get shocked than when they knew they would definitely receive a shock, confirming that anticipation is worse than the thing we are anticipating.

The study consisted of 45 volunteers who were instructed on how to play a computer game in which they would turn over rocks that might have snakes under them. Each time a snake was uncovered, the player would receive a mildly painful shock. Throughout the game, players would learn which rocks had snakes under them, allowing them to gain certainty as they made their guesses. But the cues would change intermittently, causing new waves of uncertainty, and that’s when stress was at its highest.

The level of certainty when players would flip over rocks was measured through a computational model and the level of stress players experienced as they made their choices as well as when they received shocks was measured by pupil dilation and perspiration. People whose stress levels matched their uncertainty levels ended up making correct guesses more than 50% of the time, indicating that stress can be helpful.

Why is the pain of the anticipation worse than the thing we are anticipating? We may have actually evolved to experience this pain or stress to help us make smarter, more intentional decisions to deal with uncertainty. The study’s lead researcher, Sven Bestmann, says, “Appropriate stress responses might be useful for learning about uncertain, dangerous things in the environment. Modern life comes with many potential sources of uncertainty and stress, but it has also introduced ways of addressing them.”

Think of all the apps and tools people use today to avoid uncertainty. Ride share apps tell us exactly when our taxi will arrive, tracking numbers tell us exactly when our parcel will arrive, even location sharing on smartphones can tell us exactly where our loved ones are. On the flip side, everyone has experienced the stress associated with a delayed flight, lost baggage, or not knowing where they might be able to charge their dying phone.

But is the discomfort of uncertainty holding us back from taking the risks we need to build something better?

[1] De Berker, Archy O., et al. "Computations of uncertainty mediate acute stress responses in humans." Nature communications 7.1 (2016): 10996.

FIELD SPOTLIGHTS

There are many leaders at the intersection of imagination and impact. Here are a few of the folks who inspire us across fields.

Follow the conversations

We’ve compiled lists of leaders in the space. While we can’t be responsible for what they say, we wanted to share a list of people that came up in our research.

Insider Insights

Takeaways that stuck with us from contributing experts.

REAL TALK

Ideas for action.

A lot of the challenges around change in society require collective solutions, and many of them are fueled by educational policy and culture. But we talked to the experts about what you can do, too.

HOST A GAME NIGHT TO CHALLENGE YOURSELF.

Game nights encourage open-mindedness by exposing players to diverse perspectives and novel challenges. Play can help participants to question assumptions, and embrace different viewpoints, fostering a mindset of flexibility and curiosity that can extend beyond the game table, leading to more open and critical thinking.

DIVE INTO HISTORY AND DIFFERENT CULTURES.

Exploring different cultures and history enriches our understanding of the world. It promotes empathy, dismantles stereotypes, and fosters respect for diversity. Learning from the past helps us avoid repeating mistakes, while embracing various traditions and perspectives opens doors to meaningful connections and a more inclusive future.

JOIN A “LIVING ROOM CONVERSATION”.

Belonging starts with conversation. That is the idea behind the Living Room Conversation’s mission to encourage open dialogue, active listening, and empathy. These intimate gatherings cultivate relationships, spark meaningful discussions, and create a sense of unity in an increasingly disconnected world.

ORG SPOTLIGHTS

THE ARTIST

Islenia Milien is an Afro-Latina, NYC-based illustrator specializing in conceptual problem solving and storytelling and can be easily recognized from her use of engaging composition, detail lines, and vibrant color. Her work on the OK But Why exhibit not only brought visual power to the issues, but co-shaped the ideas and perspective of the exhibit.

THANK YOU TO OUR CONTRIBUTORS

In addition to the countless authors and creators whose work we reviewed, we wanted to thank the experts who took the time to formally share their thoughts with us. While they’re not responsible for anything we got wrong, they may be responsible for a lot of what we got right!

Astrid Willis Countee, Data Anthropologist & Technologist

Crystal Dilworth, PhD, Neuroscientist & Science Communicator

Scientific Multimedia Producer (Anonymous)

ILLUMINATIONS WAS MADE POSSIBLE BY:COMMUNITY PARTNERS:SUSTAINING PATRONS:Andrew Watson

Camilla Rockefeller

David Kelley

Hillari & Michael Sasse

Wendi Zhang

CONTRIBUTORS:Astrid Countee, Research Associate

Camille Rose, Photographer

Crystal Dilworth, PhD, Board Member

Daniel Aguirre, Community Organizer

Esther Knox-Dekoning, Web Designer & Developer

Erick Salazar, Videographer + Photographer

Lindsay Newey, Animator

Kathleen Sheffer, Photographer

Maya Bialik, EdM, Board Member

Melissa Pappas, Arts & Exhibits Collaborator

Michelle Paull, Strategic Advisor

Sam Galison, Design Engineer

Samuel Knox, Software Developer

Stacey Baker, Research Associate

VOLUNTEERS:Alex Collins

Amanda Vera

Ana Ostrovsky

Andrew Graves

Bo Bradrich

David Kelley

Hillari Fine Sasse

Jimmy Maley

Kim Pedersen

Kim Tereco

Marques Jackson

Mauri Sanchez

Melissa Pappas

Michael Sasse

Negin Hemati

Pam Pedersen

Sandy Delgado

Spencer Kerber

Su Chon

Tracy Silver

Victoria Becker

Zoe Austin

THE PLENARY, CO. TEAM:Stephanie Fine-Sasse, Founder + Director

Ashley Cortés Hernández, Clubhouse Director

Christine La, Community Content Director

Samar Ibrahim, Community Engagement Manager